We know just how crazy the weather can be in Singapore—one moment it’s sweltering hot, and the next, pouring with warm, tropical rain. Temperatures and sea levels are rising steadily, and flash floods are becoming increasingly common, not just within the country, but all around the world too. For a small, low-lying island nation like Singapore, this is especially concerning.

The team:

Front row, from left to right: Ang Yang Zhi Julius (ASD), Chia Hou-An (EPD), Ishaan Nair (ISTD)

Back row, from left to right: Tan Shin Yee (EPD), Chung Zhi Xue (ASD), Clement Vimal Ravindran (ISTD), Claudia Koh Wei Ting (EPD)

Currently, we tackle these aforementioned problems with land reclamation and seawalls, respectively, but they’re costly solutions, and can be very damaging to our natural environment.

But as bleak as it may seem, the future lies ahead—more specifically, out at sea, with Seaforms by AgriArk, one of SUTD’s 2022 Capstone projects.

Designing solutions for the future

Picture this: you wake up on a Monday morning and get dressed for work, but instead of hopping on the MRT, you get on a boat that takes you out to the Singapore-Johor-Riau (SIJORI) growth triangle, where the sea city of the future is located. Made up of floating platforms pieced together in a lattice, this modular sea city is quite possibly the most sustainable solution to the challenges of land scarcity and rising sea levels.

“Our solution is actually to create these self-sustainable, floating platforms that consist of the necessary systems to sustain life, and to form a city of our future, where people can go to work,” Julius tells us.

“Our solution is actually to create these self-sustainable, floating platforms that consist of the necessary systems to sustain life, and to form a city of our future, where people can go to work,” Julius tells us.

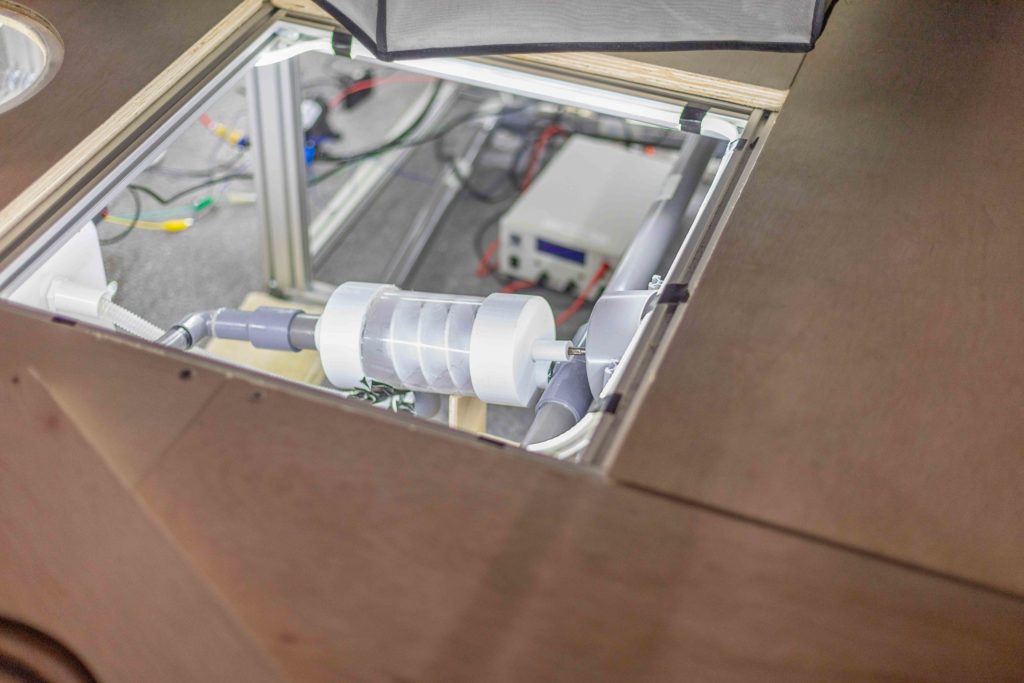

Formally known as Seaforms, these platforms are hexagonal in shape, and fitted with technological capabilities such as water filtration and energy generation systems, which form the self-sustaining foundation for the larger sea city. Sensors are also fitted at the base of each platform to allow the team to remotely monitor the physical condition of the platform, as well as the running systems. Greenhouses, office buildings, and autonomous public transport lines are then built atop these platforms.

But why stop at just being a place to work?

“That’s the main question,” Julius says. “I think most people can’t really imagine what it’s like living out in the sea, and would be hesitant about it, so by starting off working on these sea cities, they can adapt slowly, and gradually be more open to this idea of living out in the ocean.”

Another question the team often receives is about the shape of the platform—why a hexagon? Julius explains that it’s good as a modular shape, which allows the sea city to continuously expand to meet population demands. In terms of practicality, research has also shown that hexagonal platforms are the most wave-stable. Furthermore, when the sea city is set up in clusters of six platforms each, it leaves a gap in the centre of each cluster, which enables sunlight to reach marine life below, allowing the sea city to operate with minimal environmental impact.

Another question the team often receives is about the shape of the platform—why a hexagon? Julius explains that it’s good as a modular shape, which allows the sea city to continuously expand to meet population demands. In terms of practicality, research has also shown that hexagonal platforms are the most wave-stable. Furthermore, when the sea city is set up in clusters of six platforms each, it leaves a gap in the centre of each cluster, which enables sunlight to reach marine life below, allowing the sea city to operate with minimal environmental impact.

Or, as Hao An jokes, “It’s trendy.”

Refining the idea

Of course, the team didn’t conceptualise the idea of Seaforms overnight. In fact, it took about three months, or an entire term, for the team to settle on the vision for their final project.

The idea, which initially began as an urban farm on sea, was later refined during the 12-week-long Venture Building Programme—a compulsory bootcamp module that all entrepreneurship Capstone teams must complete. As part of the programme, each team had to pitch their ideas to a panel of industry mentors, who then get to decide which team they would like to support for the duration of their Capstone.

“I think what’s so special about our mentor is that he likes to think of long-term solutions that can solve world problems, and he likes to be bold. We ticked all of his checkboxes with our project, so it was a perfect match. He really taught us to not be afraid of expressing ourselves when it came to our project,” Hao An shared.

“I think what’s so special about our mentor is that he likes to think of long-term solutions that can solve world problems, and he likes to be bold. We ticked all of his checkboxes with our project, so it was a perfect match. He really taught us to not be afraid of expressing ourselves when it came to our project,” Hao An shared.

Getting down and dirty

After the initial brainstorming period came the real hard work—bringing the idea to life. Hao An tells us that by far, some of the most challenging parts of the process involved speaking with external parties and organisations, and getting them to support the team and Seaforms.

Because the project is of such a large scale (each Seaforms platform actually spans 5,000 square meters!), the team struggled to find a contractor that was willing to create a scaled-down prototype using their desired materials of concrete and Expanded PolyStyrene (EPS) for a reasonable budget.

Because the project is of such a large scale (each Seaforms platform actually spans 5,000 square meters!), the team struggled to find a contractor that was willing to create a scaled-down prototype using their desired materials of concrete and Expanded PolyStyrene (EPS) for a reasonable budget.

“A lot of them told us that we need a minimum size for the platform to be stable, and to be able to hold weight. The smallest they were willing to go was about 100 square meters, and they were quoting us a few hundred thousand dollars for it,” Julius tells us.

The team also wasn’t willing to compromise on the material of their platform, because with more affordable or accessible materials like metal, overhauls and large-scale maintenance would have to be done every three to five years to ensure the safety and stability of the platform. For a large sea city, this is not the most convenient option in the long-run.

Eventually, the team settled on creating a prototype on their own using wood and aluminium extrusion. Though this meant that they weren’t able to test the stability and buoyancy of their platform, they were determined to test the viability of the self-sustaining systems that they designed.

“We wanted to loan a hydroponics unit to test the water and energy production systems,” Hao An says. “I think I talked to 68 different farms regarding our project, and eventually, when we asked to loan a unit, only three of them responded favourably.”

“We wanted to loan a hydroponics unit to test the water and energy production systems,” Hao An says. “I think I talked to 68 different farms regarding our project, and eventually, when we asked to loan a unit, only three of them responded favourably.”

Apart from external roadblocks like these, the team also occasionally faced challenges during internal discussions as well.

“We have teammates from Architecture and Sustainable Design (ASD), Engineering Product Development (EPD), and Computer Science and Design (CSD). One thing about students of different backgrounds working together is that all of us are well-versed with our own fields, and we approach (the same) problems differently, so conflicts might arise as we’re making changes to the prototype,” Hao An explains. “There are times when you can really feel the tension, and there are times when one department has to compromise, but this is when we really get to understand each other better.”

Riding the waves of change

Moving forward, Hao An tells us that the team has big plans to further develop Seaforms. In early August, the team had the opportunity to present their prototype at the World Cities Summit 2022, where they received valuable feedback and pointers from industry leaders and professionals. The team intends to continue their work on Seaforms after graduation.

The team has also been accepted into Hyundai Motor Group’s startup programme, where they’ll receive a grant for their project, as well as the opportunity to network with other startups offline in Seoul.

The team has also been accepted into Hyundai Motor Group’s startup programme, where they’ll receive a grant for their project, as well as the opportunity to network with other startups offline in Seoul.

When asked if there is anything about the whole developmental process that they would change in hindsight, the team tells us that the imperfections of their prototype are what make Seaforms so special to them.

“There’s a sentimental value to everything we’ve done. Every decision or mistake we’ve made for Seaforms tells a story of its own,” Hao An shares. “So while the process could have been more efficient and effective, I’m pretty pleased with how far we’ve come, and I’m excited for the things that are awaiting us.”

Like what you just read?

Like what you just read?

Imagine what an SUTD education will do for you. Apply now at https://sutd.edu.sg/Admissions/Undergraduate

#whySUTD? We’re glad you asked – here’s why!

It can be hard to ask the right questions that will help you to decide which university to join, so we’ve compiled a list of FAQs for you here.